Why Bhutto matters

By Senator Sherry Rehman

Last month Pakistan played host to an important ECO summit. In the largest gathering of Asian countries the joint resolution did not mention Kashmir. As the oldest dispute on the UN docket, and as a flashpoint between two nuclear countries, there should have been no argument on the contention that Kashmir merited attention.

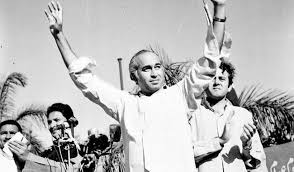

This is not how it always was for Pakistan. Flashbacks to the OIC summit that Lahore hosted in 1974 under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s (ZAB) leadership come to mind. At a moment when the Muslim world stands under siege, the absence of a statesman is felt. What would Pakistan be doing at this stage, and how would Islamabad be telegraphing its key role in re-shaping the global narrative had Pakistan’s first popularly elected Prime Minister not been executed? As the country lurches from crisis to crisis again, it seems an unavoidable question.

It is also that time of year. April 4 reminds us of the statesman that the country lost to the ambitions of a cardboard-cutout of an archtypical dictator. In forcing through ZAB’s judicial execution, Ziaul Haq snatched both our history and our future, ripped it from its evolution, and brought Pakistan headlong into a proxy jihad whose murderous spawn we cannot rid ourselves of today.

In many ways Pakistan’s innocent new generations continue to pay the price. Like Lady Macbeth’s hands, the blood just does not wash away. The existential trauma Pakistan faces today may not have stemmed from that day, but most of this murderous militant path was locked on course then. Look at the ruin about us. The smoke and blood from Sehwan in Sindh, the lawyers’ massacre in Quetta still simmers, while the APS carnage in Peshawar, and 2016 Easter in Lahore have become permanent scars. Religion has become a tool of the forces unleashed in our geopolitical search for security, and actually blurred our real security needs, both social and strategic.

Muslims are facing a dangerous world, where we are often judged by our identity and religious denomination, anguished by the bloodthirsty appropriation of a peaceful faith. Islamophobia and its exclusions are much bigger than Pakistan, but so often the dots to global episodes are landed at Pakistan’s door. In daily global discourse, the millenarian dangers of Daesh, the balkanised Middle East and its African dystopias are rarely connected to policy dominoes triggered long ago by great gaming power coalitions in Afghanistan. Pakistan became a country transformed by that encounter with proxy jihad against the Soviet Union. The arguable winning of that war cost us our peace. Yet, at the same time, no one can dispute the fact that Pakistan too became a player in those coalitions, without its parliament, without its consent, and lives today to reap that harvest.

These lost pages of our history point to roads not taken. True, it was a pre-9/11 world, where states still held the monopoly on the use of force, and non-state actors hijacking national agendas was not the norm. Pakistan was no unspoilt paradise, in fact, quite the contrary. East Pakistan had been lost not in one war of secession, but a series of exclusions and apartheids, both economic and political, that started with the language riots of 1952. Politics was a palace-led parlour game, where the voice of the hungry, the dispossessed and the landless was rarely heard. The country’s morale was at an all-time low, with prisoners of war in India, and a perilous sense of national drift. In this age of anxiety for Pakistan, like a classic tragic hero, with Promethean will and flaw, ZAB became the voice of a leaderless nation, pulling off foreign and social policy coups no one else could. Many of us still remember the Foreign Minister who tore up what was supposed to be the famous Polish Resolution on Kashmir at the United Nations, saying “my country harkens for me”. As the Prime Minister of a truncated country, he not only re-built the shattered economy, but brought back 90,000 soldiers from New Delhi’s prisons as his first task. His diplomacy gave the vexed India-Pakistan relationship the steadying hand of a statesman, with the Simla Treaty and the Middle Eastern spigot of the labour-remittance boom from the newly taking-off Gulf economies. While his government is remembered for building big infrastructure and cutting a wide swathe through bad governance, his commitment to the federation is often forgotten, sometimes deliberately so. An entire generation is fed the malicious canard that it was his ambition to assume power in West Pakistan that led to the ultimate secession of what is today Bangladesh. To the contrary, in fact, a little research will remind that after the 1970 election, ZAB had made it clear that he would prefer a democratic solution to the crisis of power-sharing between the two wings of Pakistan. Here is how it went: East Pakistan, with its higher population, had by then united behind Mujibur Rahman. On 31st October 1971, to be precise, in an interview to the Mumbai newspaper, the Blitz, Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (SZAB) made it quite clear that he was willing to lead his party into the opposition. He said, and I quote, “If Mujibur Rahman had a federal constitution, we would be happy to sit in the opposition and work in a democratic arrangement. But he wanted a confederal arrangement, and in a confederation, both sides had to have representation in the government”. Yet this point is brushed aside as is the fact that in complete contradiction to the charge sheet made to hang a man, SZAB had never sought the boycott of the National Assembly, but a small delay in its session so that space for an accommodation could be worked out before a conflagration took place in an atmosphere already muddied by high emotions and mis-representations. The Hamoodur Rahman Commission stands up to the light of day to expose hard truths, on which a panel of judges clearly examined evidence and testified to SZAB’s sincerity in attempting to avert a crisis, but that too is tossed aside in the face of a mountain of mythology spun out during the Zia years to protect a shaky regime from the power of Bhutto’s legacy.

In all the vilification that followed his judicial execution, many born after that era forget that Bhutto became the one leader who plotted a middle path for a fragmented and sect-riven Muslim world. Pakistan not only befriended Iran but also loomed large on the Middle Eastern monarchies. As the initiator of hard nuclear power he gave Pakistan strategic leverage. Many today contest its uses, but it remains the main card in Pakistan’s deterrence posture. More importantly, Bhutto should be remembered for his leadership of Pakistan, flaws and all, into a modern future where the nation could stand on its economic feet as sovereign and self-resourced.

He worked himself and his cabinet to deliver on his manifesto promises. For all those who ask what Mr Bhutto’s government accomplished, all they need to do is to talk to the 45% of the poor of Pakistan, who now live under two dollars a day, in a dangerously high statistic, where economic suicides and the selling of one’s own children has become a gruesome new statistic. These people remember a government that brought them food on their tables, that raised their wages, provided housing and jobs and schooling. Most importantly, they remember a leader and a party that addressed them directly. Today, like every terrorist targets the progressive parties, for decades every military dictator feared the legacy of SZAB. The country’s courts stand testament to state money spent on creating political alliances to keep his iconic daughter from leading a powerful government. Benazir Bhutto’s own story is a chronicle of so much struggle, yet she too embodied resistance to the enemy of her era, which morphed into terrorism and extremism. She too died as bravely as her father. If SZAB gave Pakistan the 1973 Constitution that kept the country united, the last PPP government gave it the long-delayed implementation of the diffusion of power.

This is the legacy which the young scion of the Bhutto clan must now defend, in a world riven by conflict, chaos and confusion. Because Bhutto’s party is still the only one which has paid a heavy price on the battlefield of ideas and politics. Years after ZAB’s death, his slogan of Roti, Kapra aur Makan, still resonates with the people who need it again today. The PPP is the only mainstream party that stands up with no equivocation for the rights of the most vulnerable, and it is the only party that addresses squarely the terrorism challenge of the day. Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto would have it no other way.