Italy: Venice’s Mose high water barrier could grant the survival of the city

Venice: Venice is a city of mystery and majesty. It is the floating city, the Queen of the Adriatic, the city of mirrors, and the city of masks. One can’t help but wonder how it is possible for such a place to exist.

As climate change, over-tourism, and natural conditions continue to threaten the city’s wellbeing, many fear that Venice will go the way of Atlantis, reduced to a dazzling legend.

But in 2020 of all years, Venice has been offered a chance at survival by the Mose, a decades-in-the-making system of protective floodgates.

Venice has always strived to defy the laws of nature. An engineering masterpiece, Venice sits atop wooden stilts that were driven into the ground of 118 tiny islands and marshlands over 500 years ago. Miraculously, the conditions of the lagoon have worked in Venice’s favor; over time, the clay, silt, and sediment surrounding the stilts petrified them, essentially turning them into stone.

Despite Venice’s secure stilts, the “floating city” is slowly sinking due to a natural shift in tectonic plates and external damages to the lagoon. According to World Atlas, Venice is sinking at a rate of one millimeter per year. As if this weren’t bad enough, the sea poses another threat.

Venice is routinely subjected to the beating waves of the surrounding Adriatic Sea, causing wear and tear to the exteriors of buildings. Venetians have always been accustomed to acqua alta, “high water,” a phenomenon of rising seawater mixing with storm winds and flooding the city.

The phenomenon has become more intense and frequent in recent years; the crisis of rising sea levels as a result of climate change poses a prolonged threat to the future of the city.

Tourism, the backbone of Venice’s economy, has also proven to be unsustainable for the city’s architectural wellbeing. In 2019 alone, almost five million international tourists visited Venice.

As one of the most popular tourist destinations in Italy, Venice’s delicate structure is routinely bombarded with tourist traffic. Many of these tourists reach the city by cruise ships whose waves erode Venice’s lagoon and contribute to flooding.

In 2019, after a cruise ship collision in a Venetian canal injured five people, a law was passed in Venice preventing large cruise ships from entering the city’s historic centre. Still, many fear that nearby cruise ships will continue to cause wear and tear on the lagoon.

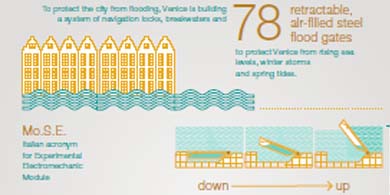

Over the years, many solutions have been proposed to protect Venice from the sea. After a historically devastating flood in 1966 in which waters around Venice rose almost 2 meters, the Italian government knew it was time to take serious action. In 1984, after years of project disagreements, the Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanic (Experimental Electromechanical Module) was proposed by the Venice Water Authority in collaboration with the Consorzio Venezia Nuova.

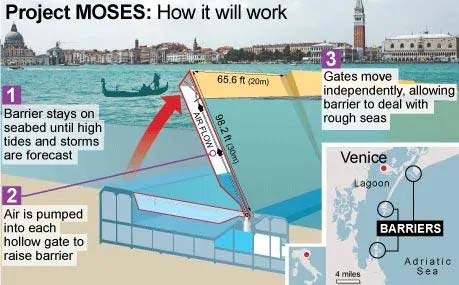

The Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanic, known by its acronym “Mose,” is a system of 78 electronic floodgates and three inlets that will separate Venice’s lagoon from the Adriatic Sea during dangerous acque alte.

Its name also refers to the biblical Moses who parted the Red Sea. The Mose will theoretically be able to protect Venice from tides of up to 3 meters. The cost of the project is estimated at 6 billion euros.

Construction of the Mose began in 2003 with the original end goal of 2011. Unfortunately, a corruption scandal threw a wrench in the process. The next projected end date was 2018, which came and went with slow progress.

Many Venetians held mixed opinions about the project. While some viewed it as important to the survival of the city, others worried that its construction was causing more harm than good. According to the Guardian, critics of the Mose believe that an artificial island built to support the Mose floodgates has hurt the lagoon, increasing flooding damages.

In November 2019, the most devastating flood since 1966 submerged Venice in 1.84 meters of water. Two people were killed and countless were injured. Damages from the flood were estimated at hundreds of millions of euros, according to Luigi Brugnaro, the mayor of Venice. After the flood, Brugnaro called upon the Italian government to take action, citing climate change as the cause of the flood.The 2019 flood motivated the Italian government to revitalize the Mose project with renewed investment. In July 2020, the Mose successfully completed its first official test run, though onsite officials said it would need another 18 months of construction, according to the BBC.

Acqua alta season usually begins in October, and 2020 was no different. On 3 Oct. 2020, the Mose was officially put to the test during a hazardous acqua alta. The Mose protected Venice from an estimated 1.3 meters of potential flooding. Notably, Piazza San Marco, usually a site of dramatic flooding, was completely protected. Mayor Luigi Brugnaro celebrated the success, saying, “Today, everything is dry. We stopped the sea.” The Mose was used successfully again on 15 October. As it is still in the final phase of construction, it will only be used for acque alte of 1.3 meters or more. Construction is set to be completed in 2021.