Italy: Rome’s third Baroque genius – Pietro da Cortona

Rome: Open any guide-book and, to reduce fame to a crude word-count, the Bs have it: Bernini and Borromini.

Or vice-versa. Part alphabetical/alliterative coincidence perhaps, part their biographically fascinating rivalry, Bernini and Borromini have tended to push Pietro da Cortona, Rome’s third Baroque genius, to the background.

Right of SS. Maria Maggiore’s altar Bernini’s simple grave-slab contains the phrase ‘DECUS ARTIUM ET URBIS’/ glory of arts and city.

The same could be said of Pietro da Cortona. Spectacular ceilings, tapestries, fresco-cycles, church and palace façades and an entire church, SS. Luca e Martina, in the Roman Forum. His work adorns Rome, and also beyond.

Like Bernini’s father, Cortona was Tuscan, together with the same-named town (Cortona) the painter, a.k.a Pietro Berrettini, is named after. And it was Florentine merchant-banker/ecclesiastical family, the Sacchetti, who supplied his first commissions.

He designed one of the family villas, the since-demolished Casa del Pigneto – out along Via Aurelia, north of the Tiber – and brilliantly reproduced it on canvas. Undepicted are the mosquitoes which would soon make the palace uninhabitable. Between the Tiber and a sail-flecked sea, the building stands spotlit by a break in the clouds.

In the Sachetti family’s second/substitute ‘casa’, 66 Via Giulia, his portrait of Cardinal Giulio Sacchetti (now in Galleria Borghese) was long the salone’s centre-piece. For the cardinal’s brother, Marcello, there were a series of early paintings eventually passed down to the Capitoline museum.

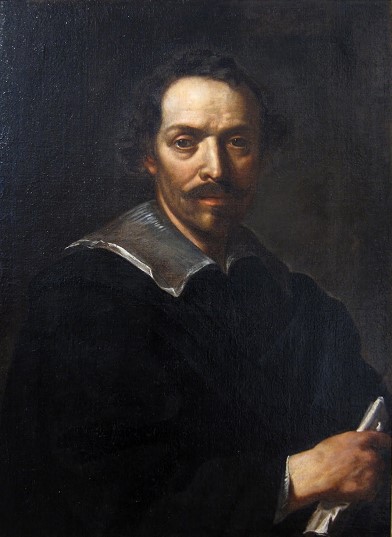

One is a haunting depiction of Marcello, a model of taste and elegance. An anxious/melancholy gaze and the left hand clutching a white handerchief suggests the illness causing the nobleman’s untimely death (1629).

Tuscan connections recurring, when Maffeo Barberini (from another exiled Florentine family) became pope, Marcello Sacchetti was appointed his general and secret treasurer. Pietra Da Cortona, talent already proven, was in the right place and at the right time, progressing from Sacchetti painter/architect to papal one.

But, unlike occasionally volatile Bernini and the infamously grumpy Borromini, Cortona with his reassuringly stable character wasn’t inclined to throw such opportunities away. To quote art historian Jorg Merz, “He moved gently through Rome’s quarrelsome artistic world, avoiding the limelight.” Writing in 1736, Pascoli (one of Cortona’s biographers) describes him as “friendly and charming, courteous and wary when he spoke of himself.”

And so to his frescoes in S. Bibiana, where in 1624, during fitful renovation work, masons came upon two urns. Given the church’s associations with the family home of the Roman martyr, the pope quickly identified the remains as the saint’s, and a favourable omen for his papacy. Sacchetti providing funding, renovation was stepped up. Bernini assumed architectural duties, Cortona that of painting one of the three naves. The church nowadays stands like an abandoned ship between Termini’s numerous rail-tracks.

‘Se piove pe’ Santa Bibiana, piove quaranta giorni e un’ settimana’ goes a local proverb. (If it rains on S. Bibiana’s Day, it’ll rain for 40 days and a week.) And Cortona’s frescoes (of the saint refusing to worship pagan gods, and her subsequent martyrdom) are interwoven with motifs depicting lush fruit and foliage.

The bucolic imagery points back to the fertility of Horti Liciniani outside, a source of herbs against nervous disorders, the saint appropriating curative powers previously attributed to the Minerva Medicina Roman temple down the road (Via Giolitti.)

Cortona and Bernini next meet in the Capitoline Museums. In Cortona’s theatrical and life-sized Rape of the Sabine Women. Like the sculptor, Cortona designed masques and stage-sets and two figures in the foreground seem familiar; their poses borrow from Bernini’s Daphne and Apollo/ Pluto and Proserpine statues. Hereby saving costs of a model?

From his apprenticeship under Domenichino, Cortona was a prolific drawer; sculptures and friezes supplied a repertoire of ready-made, dramatically-proven stances. Yet, adopting the then-fashionable idea that painting and poetry are sides of the same coin, Cortona would add any number of imaginative, sometimes humorous touches of his own.

In his Triumph of Bacchus in the Capitoline Museums, for example, an infant centaur totters on the tips of his hooves to peer inside an amphora. Offsetting the classical fixities of the temple behind is the rollicking energy of the god’s entourage. A riot of colour as well as limbs, critics citing the influence of Rubens who had passed through Rome not long before (1606-8). Cortona’s versality continues in a ‘proto-landscape’ of the alum mine to which Pope Urban had awarded the Sacchetti family a monopoly.

Inside Palazzo Barberini Cortona takes a leap in scale. Climb either stairway – Borromini’s spiral or Bernini’s grand, if-more-conventional, equivalent – the ceiling in the Salone hosts another triumph, The Allegory of Divine Providence and Barberini Power. Cortona directs a cast of hundreds.

Artist fees often depended on just that, the number of figures portrayed, here to the princely tune of 4000 ducats. Temperance, Religion and Piety personified, occupy their respective clouds. Fury, disarmed, reclines on his weapons. Dunce Titans get flunked by a spear-wielding Minerva. Crane your neck some more and there’s Hercules clubbing Avarice’s harpies. At ceiling’s centre hover, like heraldic aeroplanes, so-called ‘bomber bees’, the Barberini symbole.

Images of nepotism? Cortona a servant of power? But wait. Off to one side Silenus, the boozy centaur, appears to slip Providence’s gaze. As he’s poured another drink, the glorious slob, on transfer for The Triumph of Bacchus, almost steals the scene. Cortona, then, is a secret satirist? Except, from his sympathetic portrait of Urban VIII back in the Capitoline Museums one may hazard that the Barberini pope is smiling too.

The ceiling could have turned out differently. While Cortona was away decorating Florence’s Pitti Palace, two overweening assistants determined to complete the masterwork on their own. However their presumption was checked when the intonaco / plaster ran out, stuccatori’s / plasterers’ pay having fallen in arrears.

Urban’s papacy once ended, Barberini cardinals having fled to France, one might expect a downturn in Cortona’s fortunes. But, talent and tact ever to the fore, he was soon decorating pro-Spanish Innocent X’s Pamphilij palace/ new power-centre in Piazza Navona with “Stories of Aeneas.” Ownership currently resting with the Brazilian embassy, the fresco-cycle is visitable twice a week for guided tours in Italian and Portuguese.

Under Alexander VII, Cortona’s first Chigi commission was S. Maria della Pace.

The Baroque façade of S. Maria della Pace was added by Cortona at the behest of Pope Alexander VII. The façade of the new church, alternating concave and convex a la Borromini, conjured harmony from urban mess. Better seen than described, a confined space suddenly seemed much larger. So pleasing was this piece of street theatre’s effect that a wall-notice stipulates the design be in no way changed by future generations.

Today’s crowds keep to nearby Piazza Navona. Comparatively secluded, Piazza della Pace, matching its name, remains one of Roma’s most delightful squares. And to think Cortona claimed his architecture was a mere hobby.

Also little visited in SS. Luca and Martina. As tourists shuttle between the Roman Forum and Campidoglio, the church is easily overlooked, which is a pity, given its beautiful crypt. Cortona’s work actually began back under Pope Urban, inspired, as with S. Bibiana, by concurrent exhumation of a saint – Martina.

The remains’ authenticity has since been contested*, but initially fortune and/or providence seemed in Cortona’s favour. Until his patron, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, was accused by Innocent X of embezzlement and fled to France.

A seven year interruption ensued. After which Cortona’s work started again, this time on the upper church, including rose-stuccoed dome and the floor where he would eventually be buried.

Out of envy or no, some of Cortona’s fellow S. Luca academicians suspected a plot to turn the church, (his ‘beloved daughter’ he called it) into a private mausoleum**. The lower church was roped off and a six-year controversy broke out. Accusing the academicians of obtructionism, Cortona’s supporters prevailed, duly placing in the lower church a more fulsome wall-plaque/cenonotaph and bust.

Not that Cortona ceased painting altogether. Next door to the rippling façade of Borromini’s Oratory, S. Maria in Vallicella combines spectacle with the miraculous. Look up and one sees an expanse of (blue) sky. The church-roof, or its remains, threatens to crash down on one’s head. Only the presence of the Virgin and some strong-armed putti prevent disaster.

Cortona continued creating alterpieces. In Borromini’s S. Ivo, then in S. Carlo dei Catinari. In Pope Alexander’s 1661 refurbishment of Castel Gandolfo’s church to newly-canonised Tommaso da Villanova, he created The Crucifixion altarpiece. Working alongside him in the church was Bernini, as they had done back in S. Bibiana 37 years before.