How India views China’s diplomacy in the Middle East

Islamabad: The recent Gulf tour by Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, which included stops in the capitals of the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Kuwait, came with an offer for a new regional forum that would bring together these Arab states and Tehran. If this plan were to succeed, it would potentially herald a new geopolitical paradigm, the effects of which will be felt far beyond the Middle East.

If Iran does succeed on some level in building trust with its Arab neighbors, it would also be a secondary victory for China’s diplomacy in the region, which has taken on a more vocal and visible posture of late. However, it is not just in China’s interest to be more present as a power that is increasingly announcing itself on the world stage. Beijing’s desire for a larger footprint is also useful for powers in the Middle East that are looking to play the U.S. and China against each other. This further feeds into an increasingly bipartisan political consensus in Washington that is looking to counter its Asian competitor’s clout, specifically in areas where America’s presence has long gone unchallenged. Both China and the U.S. are transactional powers; however, for Beijing, these transactions are purely economical, and not moral or ethical.

For India, the equation is rather different. Unlike states in the Middle East, New Delhi is arguably unable to hedge in the same way, despite its attempts to build a new “multipolar” geopolitical framework. The recent state visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to the U.S. amid much fanfare made clear both the country’s developing confidence in the West and its growing anxieties over threats from an increasingly aggressive China. The deadly 2020 border clashes between India and China high up in the Himalayas not only brought bilateral relations to a precipice but also completely turned New Delhi’s strategic and security thinking on its head. Whereas earlier there was an air of agreement that India, which still conducts nearly $140 billion worth of annual trade with China, could manage its security deficit with Beijing independently, the new reality has not only recalibrated India’s view of China but also highlighted that a growing Chinese footprint globally will be detrimental to New Delhi’s interests.

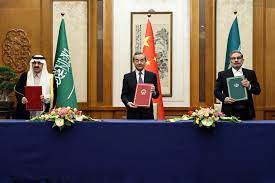

The difference in strategies being employed by India and its partners in the Middle East, including Israel, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran, poses a challenge regarding how best to cement India’s own national interests with these countries as they engage more with Beijing on issues like foreign policy, security, technology, and defense. For example, while Chinese tech companies like Huawei gain a larger footprint in the Middle East, New Delhi has restricted their access to its domestic market, especially where critical infrastructure is involved. China’s role in brokering a deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran to restore diplomatic relations after seven years has raised additional questions about what impact a potentially strong Iran backed by Chinese investments via the long-term strategic partnership between Tehran and Beijing might have on both the Arab powers and Israel alike. The Tehran-Riyadh détente, in part, answers this question with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s upcoming trip to China and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s December 2022 visit to Saudi Arabia, during which he attended the first China-Arab States Summit.

All of the above presents a challenge for New Delhi. For the moment, one indirect Indian answer to China’s growing clout in the region involves the construction of new institutions, like the I2U2 grouping (comprising India, Israel, the U.S., and the UAE). This new “minilateral” framework, with a focus on geoeconomics, high technology, and cooperation on supply-chain diversification and risk mitigation (specifically in a post-pandemic world, where reliance on China as the world’s factory is seen as a major security risk), is being supported by all the participating states. “Through our new I2U2 group, we are building regional connections to the Middle East and spurring science-based solutions and — to the global challenges, like food security and clean energy,” U.S. President Joe Biden said during Modi’s visit to Washington.

The I2U2, still in a nascent stage, is also looked upon by the likes of Israel and the UAE as a way of keeping the U.S. involved in the region. While these narratives have been regularly aired in public discourse in recent months, the role of New Delhi within the region’s security construct seems to be more independent than attached to any specific regional security architecture. Over the past months, India has conducted multiple military exercises with the likes of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, and Egypt, the scope of which has gradually expanded. The exchanges have gone from being largely conducted by the navies to include the army and air force as well, and have expanded from mere port calls to include more operational mandates aimed at interoperability.

Since 2019, the Indian Navy has been conducting Operation Sankalp, under which its warships have been tasked with providing security for Indian-flagged vessels, specifically oil tankers, as they navigate the Strait of Hormuz and Gulf of Oman amid heightened tensions between Iran, the U.S., and others in the region. The India-U.S. bonhomie is also visible in the Middle East, as the Indian Navy has stationed a liaison officer at U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) in Bahrain, with the same personnel tasked with developing India’s cooperation with the Manama-based Combined Maritime Forces, a 38-nation maritime partnership that also includes Pakistan. These developments were cemented during the April 2020 2+2 ministerial dialogue between New Delhi and Washington.

India’s approach toward the region can be seen on two fronts, strategic and economic, with both efforts running in parallel, albeit with different ambits and designs. The common factor between them is the India-U.S. partnership feeding into new minilaterals, economic ties, and relationships in the region. However, this also raises a significant question: How does New Delhi intend to manage its strategic autonomy in the region, which until now has allowed it to maintain robust relations with all three poles of power — Israel, Iran, and Saudi Arabia? China, for now, has managed to do this purely by leveraging its economic heft and regional states’ interest in using Beijing as a counterbalance to the U.S. India will need to find other ways to strike a balance, specifically in its relations with Iran, which face scrutiny and pressure from U.S. foreign policy and the sanctions regime Washington has put in place. Iran was previously one of India’s top-three oil suppliers, but New Delhi halted energy imports from Tehran both to comply with sanctions and in a show of intent to the U.S. This decision has come into question, especially after India picked up cheap Russian crude oil despite sanctions amid the war in Ukraine.

China’s presence in the Middle East will be a constant in the future, in no small part because of the designs of the regional powers themselves. While the plan may be to keep the U.S. more engaged in the region, doing so may also provide a cushion for the likes of India to maintain a degree of balance while slowly buying into the premise that countering Chinese influence in areas of interest like the Middle East will require robust collaboration to cover shortfalls in economic and diplomatic capacity. This is already visible as India and the U.S. look beyond the Indo-Pacific and the “Quad” (comprising India, the U.S., Australia, and Japan) for economic cooperation. The Middle East may be the next focus.