Is UK doing enough to monitor air pollution?

London: Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah was just nine-years-old when she suffered a fatal asthma attack on 15 February 2013.

Fast forward to 2020, and she became the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a contributing cause of their death.

Ella’s mother Rosamund had long campaigned for a second inquest after becoming convinced that pollution from heavy traffic near where they lived in Lewisham, south-east London, was a factor.

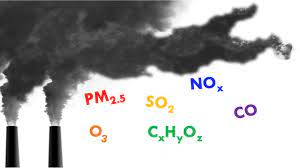

The new inquest confirmed Rosamund’s suspicions, finding that nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions had exceeded both EU and UK levels. It also concluded that quantities of dangerous particulate matter in the air (PM2.5 and PM10) had been above World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

The Deputy Coroner Philip Barlow concluded that “air pollution was a significant contributory factor to both the induction and exacerbations of her asthma”, and that “delay in reducing the levels of atmospheric air pollution is the cause of avoidable deaths”.

He also cited a shortage of air quality monitors as a reason why there was still much public ignorance about this invisible killer.

So what has changed since then, and how has air pollution monitoring technology improved?

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) says it now has 555 sites across the UK that monitor air pollution, up from 424 in 2020.

They measure some or all of the most dangerous pollutants, such as NO2, sulphur dioxide (SO2), ozone (O3), carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide (NO), and PM2.5 and PM10.

The latter two are formed of tiny airborne particles produced by vehicle exhausts, brake pads, tyre wear, combustion, and industrial processes.

Defra uses the monitoring networks to produce daily air quality forecasts on its UK-Air website.

But these public air quality systems have not developed much over the last 30 years, warns Alastair Lewis, a professor at York University’s National Centre for Atmospheric Studies, and chair of the independent advisory Air Quality Expert Group.

“We have good measurement networks for some pollutants but not for others,” he says. “For example, the volume of PM2.5 is quite easy and cheap to measure, but if you want to know what it’s actually made up of – the volatile organic compounds like chemicals from glues or paints, for example – you need a much more expensive machine costing around £100,000.

“At the moment it’s a bit like trying to measure the effect different foods have on the body by simply measuring total calorie intake.”

There are only a handful of state-of-the-art monitoring stations in the UK that can identify the constituents of PM2.5, adds Prof Lewis, despite this being the pollutant that causes “most economic damage to health at a population level.”

To explain what he means by this, he says that air pollution has an economic as well as a social cost. “Sick people are unproductive and cost a lot of money to treat, some £5bn-£15bn a year, according to Defra.”

Defra says in response that it is “investing over £10m to at least double the size of our fine particulate matter (PM2.5) monitoring network”. It adds: “This will support us to deliver further policy interventions to tackle PM2.5 and meet our stretching new targets set for this harmful pollutant under the Environment Act.”

Sarah Woolnough, chief executive of the charity Asthma + Lung UK, says that having accurate, live data from monitors is crucial for people living with lung conditions, “so they can then make day-to-day lifestyle changes, such as changing the route they walk, or the time of day they leave the house, to avoid places where air pollution is higher, and better protect their health”.

But the quality of air pollution monitoring differs significantly across the country, she argues, and needs to be “more widespread, consistent and balanced”.

Ms Woolnough adds: “The government needs to work with every local authority across the country to ensure all communities have access to a network of monitors, prioritising cities, pollution hotspots, and places frequented by vulnerable groups, like schools, hospitals and care homes.”

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, is currently embroiled in controversy over the extension of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (Ulez) to all Greater London borough.

He has defended the move, claiming that five million Londoners will breathe cleaner air as a result, and that London now has an extensive air quality monitoring system.

“The Mayor has made tackling air pollution a top priority, and is doing all he can to improve London’s air quality and resilience to climate change,” says a spokesperson for his office.

“London has one of the most comprehensive pollution monitoring networks of any city in the world. This includes more than 130 real-time, high-accuracy monitors managed by the London boroughs – which track one, some or all of the following pollutants: NO2, PM10, PM2.5, and ozone – and around 1,700 NO2 diffusion tubes which provide monthly averages.”

In addition, the Mayor has instigated the Breathe London network, which is run by the Environmental Research Group at Imperial College London in co-operation with local community groups. The network of 350 sensors is provided by US tech company Clarity.

Critics of Ulez argue that levels of NO2 and other pollutants have fallen significantly over the past decade, thereby making its extension unnecessary. They point to the mostly EU legislation that has forced vehicle manufacturers, power plants and heavy industry to clean up noxious substances at source.

Yet, clean air campaigners believe any improvement in air quality, however incremental, could save lives.

The good news is that artificial intelligence software systems are increasingly helping to analyse all the data sets we do have – traffic density, weather, time of day, pollution levels and so on. This is creating more accurate models that strip out the impact of wind, temperature and sunlight on pollution readings.

“This is really important because implementing air quality policy is expensive, so policymakers want to know which interventions are most effective. AI is helping us answer these questions,” says Prof Lewis.

For Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, who campaigns for better air quality through the Ella Roberta Foundation set up in honour of her daughter, the answer is quite simple. “Yes emissions have been falling and technology has been improving, but we need a change in human behaviour to make a real difference.

“We need to drive less and over shorter distances, but to do this we’ll need affordable, safe, reliable public transport as an alternative.”