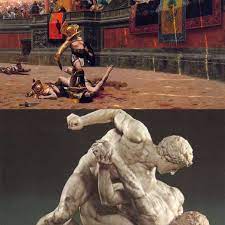

From ancient Greece to now, the bravado of athletes transcends centuries

Peter J. Miller

Athens: “I am the greatest. I said that even before I knew I was. I figured that if I said it enough, I would convince the world that I was really the greatest.” This quote from Muhammad Ali summarizes his legendary wit. But it also indicates the self-confidence and attitude that characterizes so many athletes.

Since the beginning of sport media coverage on radio and television, and now with social media providing intimate access to athletes, it has been clear that boasts, attitudes and confidence are part of the athlete persona. These attitudes, however, are nothing new.

Sport as it is practised around the globe has its origins in a partially real and partially imaginary ancient Greece. Similarly, the literary and documentary records from antiquity show that the attitudes of athletes are not a new phenomenon.

Ancient Greek athletes, however, faced a challenge unlike modern athletes. Without the internet, television, radio or any widespread means of communication, athletes had to struggle to make their success known and easily communicated to a broad public.

A white sculpture of a naked young man with a strip of cloth held in his left hand. The right arm is broken at the wrist.

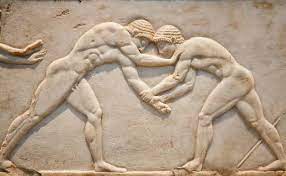

Unlike today’s elite athletes, athletes in antiquity were far less interested in highlighting sporting prowess. Athletic boasts rarely focused on how quickly someone ran, how easily they defeated an opponent in wrestling or how far they threw the discus.

Rather, athletes modified the proclamation of victory — an announcement made by a herald at athletic games, like the Olympics, that actually made them the victor. This proclamation is akin to the contemporary medal ceremony, but with more ritual and religious authority.

The proclamation contained everything necessary to celebrate an athlete: his name, father’s name, city of origin and the event in which he was successful.

The proclamation is referred to time and time again in the epinikian poetry of Pindar, an Ancient Greek poet from Thebes. Epinikian poetry consists of songs composed for a victory, as the word “epinikian,” which translates to “upon a victory,” indicates.

In the opening of Pindar’s Nemean 5, composed for an athlete named Pytheas, the herald’s proclamation is nearly repeated.

“Sweet song, go on every merchant-ship and rowboat that leaves Aegina, and announce that Lampon’s powerful son Pytheas won the victory garland for the pancratium at the Nemean games, a boy whose cheeks do not yet show the tender season that is mother to the dark blossom.”

This is a relatively simple representation of the herald. Still, the conceit of the song — that this message will go forth everywhere by means of word-of-mouth on ships — shows the determination of athletes to make their accomplishments known.

In Olympian 8, Pindar’s song claims the authority that comes from a supposed eye witness.

“He was beautiful to look at, and his deeds did not belie his beauty when by his victory in wrestling he had Aegina with her long oars proclaimed as his fatherland.”

It’s not only in epinikian song that boasts and accomplishments appear. Dozens of epigrams (poems inscribed on stone) remain from ancient Greece. Many of these leverage the proclamation, and many claim special success.

One simple example is that of Drymos, who won a running event at the Olympics in the early fourth century BC and erected a statue with an inscribed poem. “Drymos, son of Theodoros, proclaimed here, on that very day, / an Olympic contest, running into the famous grove of the god, / an example of manliness; equine Argos is my homeland.”

A weathered piece of stone with ancient Greek inscribed on the surface

Still, these seemingly simple poems often include much more. Kyniska of Sparta’s epigram, one of the only epigrams for a victory by a woman in this period, is a good example. “Spartan kings are my fathers and brothers, / but, victorious with a chariot of swift-footed horses, / Kyniska set up this statue. And I declare that I alone / of women from all of Greece seized this crown.”

Kyniska’s epigram focuses on her and her singular achievement. Its boast is unique, but the rhetoric is not. It points to the ways in which ancient athletes established records and competed with their counterparts.

Rather than counting statistical achievements, ancient athletic records tend to be of the type “the first with the most.” Perhaps most telling is the massive inscription and poem celebrating the career of the most successful athlete from antiquity, Theogenes of Thasos.

This poem builds from the proclamation to claim his incredible supremacy by winning boxing and pancration at Olympia, something “no one” had done before. He also won three victories at the Pythian Games without competition (that is, his prospective opponents chose not to bother), something “no other mortal man” had done. Last, he won two crowns at the Isthmian Games on the same day.

All of these accomplishments were memorialized in poetry and inscribed on stone, along with a massive catalogue of his victories across a 20-year athletic career.

So, as the world prepares for another Olympic year, with television networks focusing on competition between athletes, and as the social media profiles of athletes themselves turn to vaunts, boasts and rivalry, we can reflect on the notion that athletics and athletes seem intrinsically connected to these attitudes.

There are, it seems, vanishingly few continuities between the sports cultures of classical antiquity and those of today. Nonetheless, the attitudes of ancient and modern athletes remain, at their core, so very similar, despite massive change over millenia.