Sarkese: Britain’s archaic Norman language

London: There are only three native speakers of Sarkese alive – but a Czech linguist is working to document, codify and revive the island’s complex language to hopefully ensure its survival.

When you’re travelling, learning a few phrases in the local language is a good idea. But as I attempted to wrap my tongue around “Cume ci’k t’ê?”, Sarkese for “How are you?”, I knew it was highly unlikely I’d be able to use it. Because, despite being one of the most archaic Gallo-Romance languages still in existence, there are only three native speakers of Sarkese alive.

Sark is one of the Channel Islands, British Crown Dependencies that are located close to the coast of Normandy, France. Roughly 3.5 miles long by 1.5 miles wide with a population of around 500, Sark is only accessible by boat.

This relative isolation has helped to make Sark unique. It’s one of the few places on Earth where cars are banned. There is no public lighting and little light pollution, leading to it being designated as the world’s first Dark Sky Island. Until 15 years ago, it was the last feudal state in Europe. It’s also allowed the Sarkese language to retain elements that can’t be found in any other Gallo-Romance language.

Sarkese (also called “patois” by the islanders) is a unique, archaic variety of the Norman language that arrived in 1565, brought by settlers from nearby Jersey. Norman itself developed when Norse Vikings settled in what is now Normandy in France and their language melded with that of the local population.

Today, Norman languages and dialects are spoken on the Channel Islands, where English is the dominant language, and in Normandy, where French is the official language. Some Sarkese words do resemble modern French. For example, “mérsî” is the Sarkese for “thank you” and similar to the French “merci” (although its pronunciation is different), but “mérsî ben dê fê” (Sarkese for “thank you very much”) looks and sounds very different from “merci beaucoup”.

English is now ubiquitous on Sark, but this is a relatively recent development. At the end of the 18th Century, it was reported that there wasn’t a single English-speaking family.

Subject to weather, Sark Shipping operates a year-round ferry service from Guernsey. Once you’re here, rent a bike from one of several hire locations. Cycling is by far the most popular way to get around the island and there’s no better way to explore it.

In 1835, miners from Cornwall came to work in the island’s tin mines and English began to spread. After World War One, the church and school adopted English as the lingua franca. The advent of radio and TV and increased tourism meant that islanders began to spend longer engaging with the English language, and Sarkese diminished within a generation.

Elsie Courtney was born and bred on Sark and can trace her family back to the original 16th-Century settlers. She saw the decline firsthand. “When I was younger, you’d go into the pub, and they’d be talking away in patois. You knew they were talking about you, but you couldn’t figure out what they were saying,” she said with a laugh. “I think people stopped speaking it because lots of local girls and boys married outsiders. Because [their partners] didn’t speak it, it wasn’t spoken in the houses. In my lifetime it’s nearly disappeared. It was very prominent when I was a child, I’d say 80-85% spoke patois.”

Most people I spoke to told me they didn’t speak Sarkese but, it would transpire, did know a few phrases (or, often, swear words). Alongside the three remaining native speakers – Margaret Toms and Joyce Southern, both in their 80s, and 95-year-old Esther Perrée – there are also perhaps 15 semi-speakers. One of the recurring reasons I was given for the near disappearance of the language was newcomers to Sark. Yet, ironically, the person spearheading a project to save the language comes from nearly 1,000 miles away.

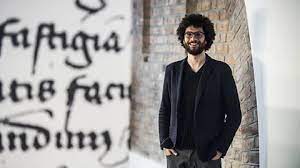

Czech linguist Martin Neudörfl has been working to document, codify and revitalise Sarkese since 2016. He first heard of the island when studying in the UK. Years later, when searching for a Norman-language project for his master’s degree thesis, Dr Richard Axton, MBE, who led La Société Sercquiaise (which works to preserve and enhance Sark’s natural environment and cultural heritage), was by chance the first contact he found.

Let’s Talk is a month-long series of language coverage across BBC.com, exploring the ancient roots of alphabets, jargon-busting the modern boardroom, and seeking to understand why we speak the way we do. Browse the whole series here.

Axton replied to his email in two days, saying, “Come as soon as you can, we need you.” Neudörfl told me that Dr Axton persuaded him to persevere with learning and recording the language. “He opened every door I needed and convinced me to continue with Sarkese. I thought it was too much, but [Richard] said, ‘It has to be you, otherwise we lose the chance to preserve the language.'”

Neudörfl has spent countless hours working with the last three native speakers to reach a point where Sarkese can be learned and taught. “We have hundreds of hours [of recordings] and our audio archive is outstanding. Even if I were to disappear, someone could revive the language just using the recordings. We’ve only achieved this through years of exhaustive research. It’s all thanks to [the speakers] for sharing their knowledge.”

Explaining the significance of the language, he told me, “I call it a window into the past… When you hear it, you know it’s one of the most archaic northern Gallo-Romance languages that still exist.

He continued: “Sarkese helps us understand other Gallo-Romance languages and even English. We’ve likely confirmed a theory from the beginning of the 20th Century [about how the pronunciation of a sound in English has evolved]. And that’s only thanks to a language spoken by three native speakers and myself.”

Teaching the language is key to its survival, but this isn’t easy. “There are so many vowels,” Neudörfl explained. “In French, it’s around 17, in Sarkese, it’s around 50. That’s why Sarkese is so, so difficult. One word can be pronounced three or four different ways.” Its complexity also likely gave rise to the popular perception that it couldn’t be written down.

To make things even more complicated, the language has different dialects. The island consists of Big Sark and Little Sark, which are joined by La Coupée, a dramatic isthmus so narrow that before railings were installed, children were forced to cross it on their hands and knees in high winds. As I leaned over the railings and looked at the beach below drenched in winter sunlight, I remembered a story Jo Birch, honorary secretary of La Société Sercquaise, had told me. She had described two Sarkese-speaking sisters who, when questioned about a difference in the language used by another speaker, said, “What do you expect? They’re from Little Sark.”

Neudörfl teaches the children at Sark School (the only school on the island) by video or in person when he’s able to travel to the island, and holds a weekly online class for adults. “So much about Sark is unique and we don’t want to lose that,” said Michelle Brady, Head of Sark School. “It’s the young generation that will keep [the language] going. So, for me, I just thought it was so important for it to continue. Martin is so good with the children as well that he’s become quite a character for them.”

This year, the students will perform a Sarkese-language play for the Guernsey Eisteddfod arts festival.

The language’s survival is especially desired by the few who have Sarkese as their first language. Perrée, one of the three remaining native speakers, summed up the precarious position of a language that has survived for centuries, and all the history and identity that’s tied up in that.

“Sarkese is important for the island and hopefully it won’t be lost. Thanks to Martin who is keeping it alive and good… it’s important to keep these things because once it’s gone, it’s gone forever.”