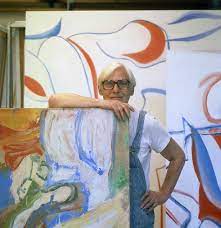

How Italy remade Willem de Kooning

Rome: Stroll across the Hofplein in central Rotterdam and you will see, just off the square itself, a piece of sculpture about six metres high and cast in bronze. This is Standing Figure.

It’s difficult to say quite what it is. At first glance, Standing Figure seems purely abstract, one of those civic works found in public spaces all over post-war Europe and unflatteringly dubbed ‘turds in the plaza’ by the American architect James Wines. Walk around the sculpture, though, and its reading changes. At times, its squishy extrusions seem like limbs, but three steps more turn them back into abstract forms. Standing Figure was made with the keen support of Henry Moore, although it is not by him. A sign nearby gives the name of the actual maker: Willem de Kooning.

On one level, this isn’t surprising. De Kooning was born in a red-brick house not far from the Hofplein in 1904. Standing Figure marks the homecoming of a local boy made good, a Rotterdammer who arrived in New York as a penniless stowaway in 1926 and is now counted among the superstars of mid-century American art. Almost everything else about Standing Figure is unexpected, though, as an exhibition this summer called ‘Willem de Kooning and Italy’, at the Accademia in Venice, will show.

De Kooning in Italy? Well, yes. If the artist was Dutch-American, Standing Figure is, in genesis at least, Italian. On a visit to Rome in the summer of 1969, de Kooning had bumped into an old friend who was working in a bronze foundry in Trastevere. On a visit there, he was invited to play with modelling clay. He fell for the material at once.

What beguiled him was the slipperiness of clay – not so much in the haptic sense (he found clay unpleasant in the hand) but in its ability to be moulded and re-moulded at will. ‘In some ways, clay is even better than oil,’ de Kooning once said. ‘You can work and work on a painting but you can’t start over again with the canvas like it was before you put that first stroke down.’

In his fifth decade as an artist when he visited Rome, de Kooning was famed for being unlike any other School of New Yorker, his work wavering back and forth between Surrealism and Expressionism, Expressionism and cubism, abstraction and figuration. Now, late in life, he himself could change form, reshaping his career as he would the small clay figures he made in Rome and took back to his studio in East Hampton, Long Island. At the age of 65, the painter was, belatedly, a sculptor.

The plasticity of clay went beyond its softness. In the 1970s, de Kooning set about playing with scale. Standing Figure had started life as small and excremental; by 1984, it was as we see it now on the Hofplein. Size was not the only transformation the work had undergone. If the new Standing Figure was monumental in scale, it was also so materially. Having had the original 10 x 20cm clay work, Untitled #4, blown up by a pair of technicians at a foundry in upstate New York, de Kooning then had it cast in bronze. From being defined by its intimacy, its scatological childishness, Standing Figure now bore the trademarks of classical sculpture.

Although Standing Figure itself is not in the Accademia’s exhibition, for obvious reasons, its progenitor is. All 13 of the original, small-scale Roman sculptures, immortalised in bronze in 1969, are there in fact. One of the most striking things about them is their heavily textured surfaces, marked with the impress of their maker’s hand. They are like finger paintings in bronze, which is to say they are painterly. The traffic between mediums would not be all one way.

If de Kooning was excited to be working in a new material in the early 1970s, he did not give up on painting. Rather, the experiments he conducted in clay and bronze spilled over on to his contemporaneous canvases. Works such as Red Man with Moustache, in the Accademia show and lent by the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, bear all the signs of the painter’s new sculptural thinking. The man of the title has a monumental feel, in part because of his height – the support on which he stands is over two metres tall – and in part because the narrowness of the canvas lends him a top-heavy gravity. The red man seems solid, modelled. He is the colour of clay.

Which is to say that de Kooning’s trip to Italy had changed not just the way the artist worked, but the way he saw. This was to do with more than the discovery of a new material. In 1983, in his 80th year, he would recall his thrill at seeing the Italian Old Masters on their own turf. ‘Titian, he was 90, with arthritis so bad they had to tie on his paint brushes,’ an excited de Kooning said. ‘But he kept on painting Virgins in that luminous light, like he’d just heard about them.’

The visual impact of seeing Venetian painters in Venice or Roman ones in Rome had been quite different from seeing them at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. ‘I remember everything half suspended or projected into space,’ de Kooning said. ‘The paintings seemed to work from whatever angle one chose to look at them. The whole secret lay in freeing oneself from the force of gravity.’

This difference had struck him on the earlier of his two Italian stays, a decade before, in September 1959. It was the first time the Dutchman had returned to Europe since 1926. Then, freedom from gravity had meant the chiaroscuro of Roman summer streets, hot daylight versus the cool darkness of cloisters and porticos. As the curator and critic Germano Celant put it, the dark-light disjuncture had seemed symbolic of Italy’s recent history. ‘American artists refocused on a culture whose roots and history could not be wiped out by the Fascist era,’ Celant wrote.

Something of both contrasts, the literal and the historical, underlies the body of black-and-white works on paper that de Kooning made in this earlier, three-month stay in the Italian capital, known collectively as the ‘Rome’ drawings. Half a dozen of these are in ‘Willem de Kooning and Italy’, all but one lent from private collections.

The words ‘works on paper’ are perhaps misleading, seeming to suggest a certain decorum. The ‘Rome’ drawings are anything but decorous. Some are in oil on paper, some in ink; some have passages of collaged paper added to them, one has been collaged en entier on to canvas. All are marked by an elegant violence.

At heart, this violence has to do with the time-honoured battle of figure and ground. Some of the drawings are in portrait format, some in landscape; all feel surprisingly three-dimensional. What de Kooning had found in the streets and colonnades of Rome was sculpture brought to life, solids and voids rendered as dark and light. As ever, the experiments he made in one medium transferred to his work in another. Paintings such as Villa Borghese and A Tree in Naples (both 1960) translate the monochrome solids and voids of the ‘Rome’ drawings into colour contrasts, cobalts and cadmiums duking it out for foreground and background.

All of which is to say that Italy wasn’t simply a source of inspiration for de Kooning; it was also a subject. His fascination with presence and absence had begun, he recalled, in New York, with its vacant lots and city blocks. ‘Even before I knew philosophy I was interested in nothingness,’ de Kooning said. ‘Emptiness, empty spaces and places.’

In Rome, these things were made concrete. The ‘Rome’ drawings may have had resonances of history and sculpture, but their maker saw them above all literally, as landscapes, images of tombs along the Appian Way. ‘This has nothing to do with what people say about my being an abstract painter,’ de Kooning insisted. As far as he was concerned, the terms ‘figuration’ and ‘abstraction’ were critical red herrings, coined by non-artists to describe the indescribable.

Italy was also post-war Italian culture, the excitement of Neorealismo cinema, of the fiction of Lampedusa and Moravia, the gritty daring of Arte Povera. You didn’t even have to fly to Rome to find it. One painting unfortunately not in the Accademia show is Excavation

(1950), in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. The painting was made nearly a decade before de Kooning’s first trip to Italy; the artist claimed that it was inspired by Giuseppe de Santis’s 1949 film Riso amaro (Bitter Rice), which he had seen in New York.

The story of two small-time criminals on the run from the law among the army of female workers tending the rice paddies of the Po Valley, Riso amaro seemed an unlikely starting point for what was at the time de Kooning’s largest painting – a behemoth measuring 2 x 2.5m unframed. Perhaps it was the bleached light of the Piedmontese landscape that caught his eye, or perhaps the moral ambiguities of the film’s story. At any rate, Excavation marks what was then a high point in de Kooning’s hybrid style, its entirely abstract composition being made up of things that seem entirely representational: human noses, eyes and teeth, necks and jaws; shapes that read as fish and birds.

These shimmer across the painting’s surface like hieroglyphs, defining it while at the same time evoking further planes beyond it. Just to add to the work’s ambiguities, recent scholarship has found that Excavation was actually finished before Riso amaro opened in New York, so de Kooning’s claim about the film’s influence was technically impossible. (This could have been a lapse of memory. A review of the movie ran in an issue of Life magazine that also carried an article about the excavation of Manhattan’s subway stations. De Kooning may simply have conflated the two.) The painting was finished in June 1950, just in time for it to be shown at the 25th Venice Biennale. As ‘Willem de Kooning and Italy’ has been timed to coincide with the 60th Biennale, it is a shame that Excavation can’t be there.

The exhibition opens a fortnight after the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s Rothko show closes (see Apollo October 2023) and is in many ways pendant to it. In the first decade of the Cold War, art history in the United States was written to exclude European influence from American art. America having won the war, it must now be seen to win the peace: Abstract Expressionism was to be homegrown, its historiography nativist. That both Rothko and de Kooning were born in Europe was an inconvenience; the latter having spent his first 22 years there was particularly problematic.

The answer among writers such as Clement Greenberg was to Americanise him as a wild man, an alcoholic to compete with that impeccably Midwestern lush, Jackson Pollock. In the words of one US critic, de Kooning ‘was a painter’s painter and a drunk’s drunk’; to which might have been added a misogynist’s misogynist and a womaniser’s womaniser. It is only with the passing of years that a more subtle view of his life and work has emerged. This new Venice show will add to the nuances.

It also, perhaps unknowingly, does what many larger exhibitions have failed to: it consolidates de Kooning as a single artist. Art history likes neatness. One of the problems of getting a handle on de Kooning has been his untidiness. There are so many apparently contradictory de Koonings – the figurativist, the abstractionist, the Expressionist and Surrealist; the colourist and master of monochrome; the painter and sculptor. By viewing him through the unifying optic of Italy, and the many things Italy meant to him, the Accademia manages to show us not just an unexpected master, but a coherent one.