Italy marks its liberation day amid censorship row

Rome: Italy celebrated its liberation from fascism, an anniversary overshadowed by a censorship row at the public broadcaster centered on Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

RAI, which has several TV and radio stations and is funded in part by a license fee, canceled a monologue on fascism by a renowned writer due to be broadcast for Liberation Day.

Critics have for months said that RAI has appointed figures ideologically close to Meloni’s government, dubbing it “Telemeloni.”

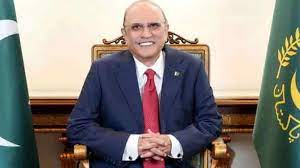

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni speaks following a summit in Brussels on Thursday last week.

The decision to pull Antonio Scurati’s monologue, in which he accused Meloni’s party of rewriting history, sparked widespread outrage.

“This RAI is no longer a public service, but is being transformed into the megaphone of the government,” Democratic Party leader Elly Schlein said, echoing a phrase used by RAI’s journalists’ union.

Meloni herself, who leads the Brothers of Italy party, denied censorship on her part — and responded to the row by posting Scurati’s monologue on Facebook.

She suggested that Italians decide for themselves, while making clear what she thought of him.

“Those who have always been ostracized and censored by the public service will never ask for anyone’s censorship,” she wrote.

“Not even those who think that their propaganda against the government should be paid for with citizens’ money,” she added, referring to reports that Scurati wanted to be paid too much.

April 25 is an emotional time for many Italians, marking the insurrection in 1945 that reclaimed several northern cities from Nazi invaders and their fascist collaborators, and the liberation of the rest of the country by the Allies.

In his monologue, Scurati accused Meloni’s party of “trying to rewrite history” by blaming the worst excesses of the National Fascist Party rule on its collaboration with Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

Meloni told parliament when she took office that she never felt any sympathy for regimes, including the National Fascist Party led by Benito Mussolini between 1922 and 1943.

On Sunday, Scurati read his monologue to a live audience in Naples and accused Meloni of painting a “target” on his back by using her platform to “personally attack” him.

The Strega-prize winning writer ended his speech by echoing a call from some in the audience: “Long live anti-fascist Italy.”

As a public broadcaster whose top management has long been chosen by politicians, RAI’s independence has always been an issue of debate, but the arrival in office of Meloni has redoubled those concerns.

Just months after she took office, RAI’s then-chief executive officer Carlo Fuortes — appointed by former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi — resigned, complaining of a “political conflict” over his role.

In his place the government appointed Roberto Sergio, who said he intended to air “a new narrative.”

In December last year, senior RAI editor Paolo Corsini was heavily criticized after appearing at a Brothers of Italy meeting, where he aligned himself with Meloni’s party.

Earlier this month, the European Federation of Journalists expressed concern at a change in rules on political balance allowing more air time for ministers discussing government business on RAI ahead of the European Parliament elections.

One RAI journalist, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that “the climate is unhealthy.”

Over the weekend, the union of RAI journalists, Usigrai, accused managers of trying to “silence” Scurati and of a wider “suffocating control system that is damaging RAI, its employees and all citizens.”

However, RAI director-general Giampaolo Rossi on Monday condemned the idea of censorship as “completely baseless.”

He said an investigation had been launched into how Scurati’s monologue was canceled — while condemning “surreal reconstructions” surrounding “yet another attempt at aggression toward RAI.”

The broadcaster’s schedule aimed at guaranteeing the “greatest possible heterogeneity of stories,” he added.