The Italian waiter who nearly destroyed MGM

In 1990, a former waiter went from Italy to Hollywood and bought MGM for $1.3bn. Then brought it to its knees.

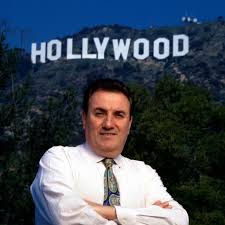

Now aged 83, Giancarlo Parretti looks like a well-off yet perfectly ordinary gentleman. There’s a twinkle in his eye as he walks around his spacious townhouse in Orvieto, Italy, showing off his huge library of books, film memorabilia and expansive art collection. But behind his shuffling gait and easy smile lies the steely resolve that led him from relative poverty to multi-millionaire success – and from washing dishes to buying one of Hollywood’s most famous movie studios.

The story of Parretti is entertainingly brought to life in John Dower’s new documentary, The Man Who Definitely Didn’t Steal Hollywood, which appeared on BBC iPlayer on the 18th October. That amusingly off-kilter title is a sign of its subject’s aforementioned steeliness; from Dower’s earliest interviews with Paretti to the last, the documentary’s name comes up again and again.

Parretti preferred “The Man Who Came From Nothing” – the subtitle of his autobiography – or perhaps “I Conquered Cinema In America”. But definitely not “The Man Who Stole Hollywood,” the title Dower insists was chosen for him by the BBC. Something about the suggestion that he was involved in theft seemed to make the otherwise affable Paretti distinctly ill-at-ease.

Other than his finickiness about titles, the other thing that can be safely said about Parretti is that nothing about him is quite as it seems. He talks about his difficult upbringing – how he was left outside a church as a newborn baby, like something out of a 19th century novel, and raised by another family. How he went from washing dishes in Italy to waiting on Winston Churchill at an upscale hotel in London, to actually owning an entire chain of hotels by the late 1980s.

The trouble is, nobody in Dower’s film can quite pick apart which bits of Parretti’s story are true and which are, shall we say, self-mythologisation. Nor is it entirely clear just where all his money initially came from; Parretti denies having links to organised crime, though one subject in the documentary argues that he wouldn’t have been able to acquire a Sicilian football team without the blessing of the Mafia.

Wherever the money came from, Parretti was wealthy enough to be described as a ‘tycoon’ (among other less favourable adjectives) in the 1990s. By the early part of the decade, he’d bought himself a $9m mansion in Beverly Hills along with various other trappings of wealth, including a Rolls-Royce and a private jet. Having pumped some $100m into the struggling Cannon Films in the late 1980s, he now had in his portfolio an independent studio and a chain of cinemas spread across the UK and Europe. Seemingly from nothing, Parrretti had built a miniature empire.

It was thanks to this high-rolling lifestyle that he was able to consider getting the financing together to buy MGM/UA, a once mighty studio that had begun to falter to such an extent that its owner, Kirk Kerkorian, decided to put it up for sale in 1990.

In fact, Parretti says in Dower’s documentary that he was coaxed into buying MGM as a bet following a chance encounter with Gianni Agnelli, the boss of Ferrari and Fiat, and former US secretary of state, Henry Kissinger. Parretti claims he was invited to sit with the pair for dinner at an expensive New York restaurant one day, and that Agnelli had joked about Parretti being wealthy enough to buy MGM. When Kissinger laughed disbelievingly, Parretti agreed to bet on it. If Parretti managed to acquire the studio within the next six months, then Kissinger would have to buy dinner for everyone. Like so many chapters in Parretti’s life, it’s impossible to know whether or not the anecdote is true.

Through a murky series of dealings, though, Parretti really did manage to get together the roughly $1.3bn he needed to buy the studio. Industry observers were somewhat flummoxed; few even knew who Parretti was. “This is one of the most enigmatic deals in Hollywood,” said entertainment analyst Paul Marsh in archive footage from the period. “We don’t know where the money’s coming from.”

Not long after the purchase, things went sour. Parretti, although fuelled by boundless self-confidence, appeared to know little about running a major film studio. He set about merging MGM with Cannon Films, and in the process of doing so, made brutal cuts to the former studios’ employees.

“We had 250 people too many,” Parretti says in Dower’s film, before marvelling that the United States’ lack of staff protections meant he could make people redundant at a moment’s notice.

Over 270 jobs went at MGM/UA within weeks of Parretti’s arrival. Amid the chaos of departing staff, many from the studio’s accounting team, MGM stopped paying its bills. According to Fortune magazine, the studio was “running a cash flow deficit” of as much as a million dollars per day. Big-name stars weren’t being paid, either. A six-figure cheque was given to Dustin Hoffman in January 1991, which subsequently bounced. Sean Connery essentially went on strike because he was owed money.

The financial turmoil also meant that MGM’s film output shrank to almost nothing. The release of Ridley Scott’s Thelma & Louise had to be postponed because the studio simply didn’t have the funds to put it in cinemas. What would have been Timothy Dalton’s third outing as James Bond, billed as Property Of A Lady, was so heavily delayed that it was scrapped altogether; a lengthy legal battle between producer Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and distributor MGM ensued over the latter’s “highly irregular” handling of Bond, and the 17th film in the franchise, GoldenEye, didn’t emerge until 1995. By then, Dalton was out and Pierce Brosnan was in.

Amid reports about Parretti’s nepotism (he gave his 21 year-old daughter a senior role in accounts department) and using company money to fund his lavish lifestyle (including paying ‘development deals’ to women he was having affairs with), MGM was taken to court by a Los Angeles lawyer named Stephen Chrystie. He’d been approached by several clients who’d said they hadn’t been paid by MGM; Chrystie therefore filed suit against the studio, the aim being to force it into involuntary bankruptcy. The clients affected would then be paid from the proceeds of its liquidation.

Ultimately, Parretti was forced to resign from the studio at the insistence of Credit Lyonnais, the French bank which had bankrolled approximately half of the $1.35bn MGM purchase. It was later reported that the bank was keen to avoid MGM filing for bankruptcy in large part because it wanted to avoid a deeper investigation into its affairs.

Around the summer of 1991, the FBI and the Securities and Exchange Commission began looking into Parretti and where his money came from, and before long, stories emerged that officials at Credit Lyonnais had been essentially bribed into loaning billions of dollars to both Parretti and other major players in the Hollywood film industry. When it looked as though Parretti could go to prison, charged with perjury and falsifying evidence, he fled to Mexico and took a plane back to Italy.

For years afterwards, MGM continued to teeter on the brink of oblivion, rescued now and again from cash injections and lines of credit; in a bizarre twist, Credit Lyonnais decided to sell MGM in the mid 1990s, and its purchaser was none other than Kirk Kerkorian – the businessman who’d sold the the studio years earlier.

By the end of the 1990s, a fuller picture of Parretti’s financial mischief began to emerge. The huge network of valuable companies said to be owned by the businessman and his accountant Florio Fiorini (who was jailed for fraud in 1992) were largely shell companies. As one lawyer who investigated Parretti said in Dower’s film, “This whole thing was just a sham to generate entries on books and records – false accounting to look like they actually had value when all they were carrying were… billions of dollars in debt.”

Parretti was found guilty of fraud by a French court in 1999 and sentenced in absentia to four years in prison. All told, it’s thought that Parretti syphoned perhaps as much as $100m from MGM; unsparing in its description of the financier, Fortune later described him as a ‘predator’ and a ‘thug’ and called the purchase of the studio “the biggest Hollywood swindle ever.”

It’s an extraordinary story, and one entertainingly told by Dower. Through it all, Parretti sits in his grand-looking house, surrounded by priceless paintings by the likes of Picasso, Dali and Miro. Even here, things may not be quite as they first appear: back in the 1980s, Parretti had given Time Warner chairman Steve Ross a drawing by Picasso as a gift. Ross later had the painting looked at by an expert, who concluded that it was a fake.