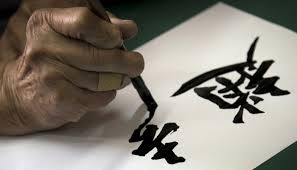

Handwritten Signs Preserve a Unique Cultural Essence: Hong Kong’s Calligraphy Faces Extinction

Da Kung Central Plains

In Sheung Wan, the terrazzo signs and advertisements of the traditional cured meats shop Yu Kee Hap—crafted by calligrapher Au Kin-kung in the 1930s—stand as a testament to a fading art form.

The Disappearing Art of Hong Kong Typography

Hong Kong’s distinctive calligraphy, an integral part of its cultural identity, is rapidly vanishing. Neon signs are dismantled, handwritten minibus destination plates are replaced with digital fonts, and hand-carved mahjong tiles face extinction due to a lack of successors.

The root of this decline lies in the diminishing practice of Hong Kong’s commercial calligraphy. With computers taking over, calligraphers no longer rely on creating handwritten signs for a livelihood. This shift threatens not only an art form but a cultural legacy embedded in every stroke.

To shed light on this decline, Hong Kong Wen Wei Po interviewed Wong Shun-yau, author of The Ink Traces of Hong Kong. Wong also leads the “Ink Traces” research project, aiming to preserve and study the city’s unique calligraphy and typography.

Calligraphy’s Evolution from Commerce to Art

Today, what was once commercial calligraphy often appears in art exhibitions. One such display featured a sketch of a handwritten signboard from the 1990s at the “Cross-Border” design exhibition.

During the interview, Wong met the reporter at Po Leung Kuk, a site housing works of renowned calligraphers. These pieces reflect Hong Kong’s rich cultural history.

The Digital Threat to Handwritten Typography

Hong Kong’s typography reflects its vibrant, multicultural heritage. Wong explains, “Handwritten and hand-carved fonts carry a unique ‘spirit.’ In the past, business owners sought calligraphers to craft their signs, believing the human touch imbued their work with life, something machines and computers cannot replicate.”

Wong emphasizes that traditional signboards carry the “spirit” of the calligrapher, the sign maker, and the business owner—a symbiotic relationship foundational to Chinese commerce.

From Elite to Everyday Art

In an era of low literacy, merchants displayed calligraphy as public art, transforming elite creations into accessible masterpieces. However, dwindling numbers of skilled calligraphers and engravers have made such works costly and rare.

Since 2020, Wong has been collecting works by 20th-century calligraphers like Au Kin-kung and Tse Hei, analyzing their blend of artistry and commerce.

Preservation Challenges

The fading transmission of calligraphy skills has led to the loss of unique styles. To counter this, the “Ink Traces” project reconstructs historical teaching methods. But Wong warns that time is running out as older masters pass away.

Hong Kong’s highly commercialized society poses another challenge, with traditional calligraphy losing ground to modernization. Institutions like Po Leung Kuk are among the few remaining bastions of calligraphic heritage.

“Everything leaves traces,” Wong says. The “Ink Traces” project has preserved over 80 years of Hong Kong’s history, ensuring the legacy of this intricate art form for future generations.