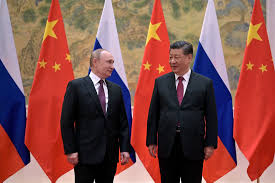

China and Russia Will Not Be Split

MICHAEL McFAUL is Professor of Political Science, a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, and Director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. From 2012 to 2014, he served as U.S. Ambassador to Russia. He is the author of the forthcoming book Autocrats vs. Democrats: China, Russia, America, and the New Global Disorder.

EVAN S. MEDEIROS is Professor and Penner Family Chair in Asian Studies at the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and a senior adviser with The Asia Group. He served as Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Asian Affairs at the National Security Council during the Obama administration. He is the author of Cold Rivals: The New Era of U.S.-China Strategic Competition.

Many American foreign policymakers dream of being the next Henry Kissinger. Whether they admit it or not, they look to him as the model of shrewd calculation of national interests, geopolitical acumen, and devotion to diplomacy. He was a leader who struck grand bargains with global effects. And no diplomatic maneuver is more quintessentially Kissinger than the U.S. opening to China in 1972.

As great-power competition heats up again, today’s U.S. policymakers may be tempted to try to replicate that success by orchestrating a “reverse Kissinger”—pulling Russia closer to balance a rising China, in a reversal of what Kissinger did beginning in 1971, when he was serving as national security adviser to President Richard Nixon. In an influential paper published in 2021 by the Atlantic Council, the anonymous author, a former government official, proposed that Washington “rebalance its relationship with Russia” because “it is in the United States’ enduring interest to prevent further deepening of the Moscow-Beijing entente.” In its first few months, the Trump administration has seemed to warm to this idea. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has called for the United States “to have a relationship” with Russia rather than let it “become completely dependent on” China. Running a “reverse Kissinger” is also the perfect alibi for President Donald Trump’s courtship of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Americans dislike Putin, but if Trump’s embrace of the Russian dictator can be presented as pragmatic, realpolitik, or otherwise Kissinger-esque, they might accept it.

In the abstract, drawing Russia away from China to shift the balance of power in favor of the United States sounds appealing. In reality, the idea is a bad one. Most important, the analogy to the Cold War of the 1970s is flawed. Back then, Washington recognized and exploited, rather than produced, a deep Sino-Soviet split to improve relations with Beijing. Not only does such a split not exist today, but Beijing and Moscow are now true strategic partners. Both Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping see the United States as the greatest threat to their respective countries and have built an institutionalized relationship based on converging material interests and common autocratic values. Putin has no reason to give up China’s extensive, concrete, and reliable support to Russia’s civilian economy and defense industry in exchange for ties to Washington that may not last past the end of Trump’s term, in 2028.

Moreover, in the improbable event that the United States could peel Russia away from China, a new rapprochement with the Kremlin would bring few real benefits to the American people and come at a steep cost to other U.S. interests. Putin would never help the United States deter or contain China. Instead, he would leverage American eagerness for better relations to play Washington and Beijing off each other as he rebuilds Russia’s economy and military. Even the process of courting Moscow would be damaging because any favor the United States shows Russia alienates Europe. Militarily, Russia has far less to offer the United States than NATO does, and it is an inferior trading and investment partner compared with the European Union. Trying to win Russia over would mean swapping a strong, rich, and dependable set of allies for a weak, poor, and fickle partner. It is an exchange Kissinger, a committed realist, would never have made.