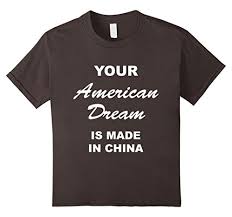

American dream’ shot and produced in China

New York: Having spotted his latest video playing on a huge LED screen in the Times Square down below, Justin Scholar bolted from his chair and rushed out his iPhone trying to record it through the giant window of Xinhua North America’s office at the top floor of a high-rise in Midtown Manhattan, New York City.

The interesting episode took place when the 25-year-old young man from U.S. state of New Jersey was wrapping up an interview with Xinhua.

“It’s sort of the American dream to see your name up in lights, right?” said the excited video producer and musician.

The video that helped Scholar fulfill his “American dream” was shot and produced in China, where Scholar is living and working as a media company owner.

After taking his first Mandarin class back in high school seven years ago, Scholar listed China as a future destination and made his first trip to Shanghai in 2015 through a study-abroad program when he was a student in New York University.

“Shanghai is an incredibly efficient, modern city,” said Scholar. “To have this impeccably accurate and fast metro and to have very clean streets and bright lights at night, and people pouring in by the thousands … that’s just a success story of a millennium.”

The young man fell in love with the city, where he ate a lot of authentic “xiaolongbao” or little steamed meat buns, and felt safe walking on the street at 3 a.m. He spent most of the time learning ink and wash painting, calligraphy and Chinese instrument Guzheng, which enriched his set of artistic skills with a touch of eastern aesthetics.

Scholar felt Shanghai’s call for greater business prosperity with foreign participation as the local government “opens its doors, offering new business visas and new incentives for businesses to come.”

He chose to go back to Shanghai on his 24th birthday with an aspiration to launch his own company when his career at home was already thriving after making commercials for big names such as Coca Cola and Jaguar.

“I really felt inspired to go back. And finally I tell them, this is what’s in my heart; this is what I want to do. It feels like every ounce of my body is saying, go back to China. Your dream is there. Your life is there,” Scholar said.

So far, the company Scholar started with his Chinese business partner has produced some 15 videos for pop icons, fashionistas, and art museums. The video that plays at Times Square — a tourism promotional film for southwest China’s Chongqing city, was their first project contracted by a local government in China.

After graduating from Columbia University in 2012, Zak Dychtwald embarked on a journey of exploration to China, where “everyone was saying the future was happening.”

“The China that was being described to me back home was worlds apart than the China that I was actually experiencing,” the 28-year-old from the U.S. state of California said.

Dychtwald has recently relocated to New York City where he has founded a think tank and consultancy focused on “Young China” — providing a unique lens for American businesses and organizations to better understand and grab China opportunities.

There are over 300 million English learners in China — mostly millennials, compared with 1 million Chinese learners in the United States and the drastic comparison contributed to a significant imbalance of mutual understanding between the two countries as “language has been a great proxy for understanding,” Dychtwald said.

The American young man who speaks fluent Mandarin was impressed by his Chinese peers’ unparalleled life experiences during his course of research in various parts of the country.

“There’s this young generation who feels that they, as a people, as a culture are on the rise, that they’re proud to be Chinese, that they don’t necessarily want western stuff just because it’s western … There’s recognition that what China’s creating today is special and worth being proud of,” said Dychtwald.

Many of the Chinese millennials grew up watching western movies, TV series, following western fashion, and have developed a “nuanced” and “intimate” understanding of western culture, he said.

Apart from language barrier, Dychtwald said many Americans are still harboring a perception of China “that’s still stuck in the 1990s and 2000s,” and his American peers were brought up by a generation who were somewhat influenced by a Cold War mentality.

“My hope is that there is more effort from both sides to create real understanding, not just (of) slogans, not just (of) political speeches, but of people,” he said, adding that he hopes to help build the bridge between the world’s two biggest economies.

“Me personally, I definitely wouldn’t be where I am without the Confucius Institute,” Carrie Feyerabend said, recalling her unbelievable journey of learning Mandarin and Peking Opera since 2010.

Brought up in Skaneateles, a small town deeply locked in New York State, Feyerabend studied Peking Opera in Beijing and now serves as an assistant to the director of the Confucius Institute of Chinese Opera (CICO) at Binghamton University (BU).

Despite her major in Spanish at BU, Feyerabend chose to learn Chinese, because it was a difficult language and she wanted to challenge herself.

Given her excellence, CICO picked Feyerabend to participate in Chinese Bridge, or the Chinese Proficiency Competition for Foreign College Students.

The second time she participated in the beginners round in the United States in her sophomore year, she won first place and gained the opportunity to go to China to study Peking Opera at the National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts (NACTA) in Beijing for a semester.

She is now a superb Peking Opera singer and dancer with Shuixiu, literally Water Sleeves, one of the most skillful stunts in Peking Opera.

According to Feyerabend, learning the Chinese culture has not only facilitated her interaction with Chinese people, but also helped her associate with people from all over the world.

“I personally try to live by a guideline that you can’t judge a book by its cover. You never know what’s lying underneath,” she said. “The only way to know what’s lying underneath is to have conversations with people, get to know their story and get to know their background.”

The Confucius Institutes in the United States are a fantastic resource for students to go beyond the classroom, interact with Chinese teachers and learn about different aspects of Chinese culture, she said.

Scholar, Dychtwald and Feyerabend are among hundreds of thousands of young Americans that seek golden opportunities as a result of China’s reform and opening up in the past four decades.

As an ancient Chinese proverb goes “one generation plants the trees in whose shade another generation rests,” the younger Americans as well as Chinese are benefiting from the tremendous dividends of the mutually beneficial bilateral ties.

Reflecting on his own story, Scholar encourages more young Americans to explore the outside world to gain a more fulfilling life experience and he strongly recommends Shanghai and other booming Chinese cities to young entrepreneurs and artists.

In his opinion, young people of both countries could play an essential role in promoting bilateral ties by studying in each other’s country and developing “real mutual understanding between youth culture.”

“My kids will probably end up speaking Chinese, and a lot of young Chinese people will say, ‘my parents studied in the United States,'” said Scholar. “I really like to think that America and China will develop a very strong relationship.”