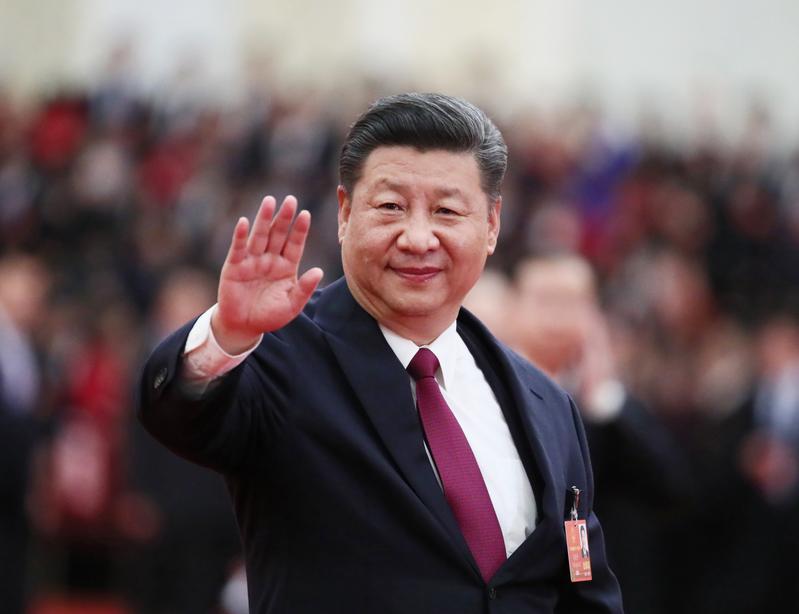

Xi Jinping and “the taste of home”

Beijing: Ahead of the Chinese Lunar New Year of 2015, Liang Yuming prepared lunch at his home for a special guest — Chinese President Xi Jinping.

“I served him rural home cuisine. We had pickled vegetables, fried cakes, chicken, mutton, pumpkin… He ate half a bowl of pickled vegetables. He loved it,” said Liang, villager of Liangjiahe in Shaanxi Province, northwest China.

Xi, also general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and chairman of the Central Military Commission, returned to this small village on the Loess Plateau on Feb. 13, 2015 during an inspection tour in Shaanxi to extend Spring Festival greetings to locals. For nine years in a row since 2013, he has made it a tradition to visit ordinary people ahead of the most important holiday on the Chinese calendar.

Xi lived in Liangjiahe starting from 1969, just one among tens of millions of urban educated youths who were sent to live and work in the countryside.

During the seven years he lived there, pickled vegetables were a staple of most meals. He led a life as humble as the food on his plate.

“When Xi stayed in Liangjiahe, he often ate at my home. Life was difficult, and there wasn’t much to eat,” said Zhang Weipang, Liangjiahe villager. “We ate steamed buns made of corn and bran, and sorghum noodles. In winter, we ate pickled vegetables and we could eat it for six months. Every household made two jars for the winter.”

The pickled vegetables of Shaanxi are mixed with salt and allowed to sit for 20 days. Its simplicity produces what Xi calls “one of the most delicious food.”

“I haven’t eaten pickled cabbage for a long time, and I really miss it,” Xi said.

After becoming Party secretary of Liangjiahe in 1974, he spearheaded a series of social initiatives that benefited villagers, including building a dam and a methane tank.

“He was too busy to cook. So he ate with my family. He gave us all his monthly ration of 20 kg of grain. We ate together. He was never a picky eater. He ate whatever we cooked,” said Zhang.

Decades later, the leader of hundreds became the leader of 1.4 billion; it gave him a taste of things to come. It was in Liangjiahe that a 15-year-old who, in his own words, “knew nothing,” learnt how to live and work.

“He’s such a person. He can swallow the worst food, and he always respects even the poorest people,” said Zhang.

Xi’s years in Liangjiahe cemented a concern for food security and nutrition. Life for the villagers was hard, often no meat would grace their tables for months.

“One thing I wished most at the time was to make it possible for the villagers to have meat and have it often,” said Xi in a speech in Seattle, the United States, on Sept. 22, 2015, when he recalled his early days in Liangjiahe.

Today, for hundreds of millions across the country, meat is no longer a luxury as China has made decisive progress in ending absolute poverty.

Understanding what people eat is an important part of Xi’s inspection tours across the country. It has given him insight into how people really live.

During an inspection of Shaanxi in April 2020, Xi walked into Xi’an Restaurant on a commercial street and saw diners feasting on Shaanxi’s signature dishes. “These are all the tastes of my hometown,” he said.

“As the Chinese saying goes, food is the first necessity of the people. We feel that the general secretary really cares about people’s livelihood, and loves his hometown,” said Xu Haijun, executive chef of Xi’an Restaurant.

Food has also been a powerful tool in uniting people. When meeting Lien Chan, former chairman of the Kuomintang Party, in 2014 in Beijing, Xi served Lien, who was born in Shaanxi Province, to typical regional dishes including mutton soup and noodles, and the two chatted in the local dialect.

During a state visit at the invitation of Xi in 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin tried his hand at making local snacks from the city of Tianjin.

Later that same year in Beijing, Xi presented another Shaanxi specialty to his guest. This time, it was Fu tea and it was served to former British Prime Minister Theresa May.

Fu tea was popular among nomad people whose diets contained a lot of meat and dairy products. It was one of the most sought-after items traded along the Silk Road in northwest China, central Asia and Europe.

Digestive Fu tea, mutton soup, noodles, pickled vegetables… Food can be said to have sustained Xi’s closeness to the people, and nourished China’s relationship with the world.